During the Great Depression, my family was

fortunate to have access to valuable resources. We lived near the sea and my

father was able to maintain his job, although his salary was reduced to only

$50 a month, a third of his previous earnings. Fortunately, he was also a

skilled hunter and fisherman, which provided us with a reliable source of food.

We even had our own fishing boat to catch fish for our meals. In addition, we

were fortunate enough to have a small barn where we raised two pigs for meat and

a cow for milk, cream, butter, and cottage cheese. We were constantly reminded

of how lucky we were to have these provisions during such a difficult time. Our

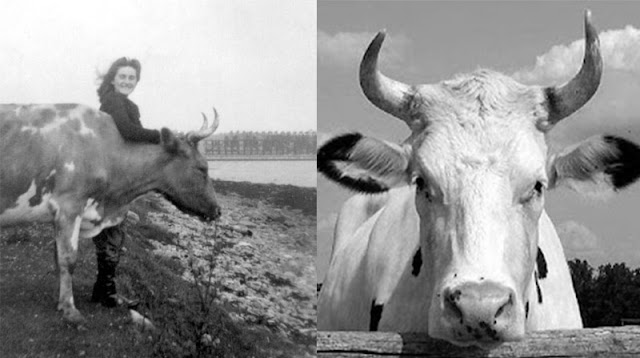

cow, Blossy, was a beautiful Jersey cow who was a beloved part of our family.

It was my responsibility to take her to the pasture every morning before

school. I would lead her on a rope to the pasture, which we rented for only

$3.00 a year. Blossy was a gentle and kind cow with the most beautiful eyes,

and it was always a pleasure to care for her. She never caused us any trouble.

In the evening, I would bring her back home for the nightly milking and keep

her in the barn until morning. It was a chore to care for the milk, and my

mother mostly took charge of this task. We had a separator to separate the

cream from the milk, and the extra milk was stored in large black pans until

the cream rose to the top. My mother would then scoop off the thick cream with

a spoon. Jersey cows were known for their high-quality cream. Later in the day,

we would use an old wooden butter churn to make our own butter. The remaining

milk was used to make curds, which were then hung to dry on the clothesline and

turned into cottage cheese. Curds and cream were a delicacy in our household.

Although we had an abundance of food, including homemade bread twice a week, we

also had salt fish and pork. My mother always reminded us to "go easy on

the butter," but my siblings and I couldn't resist smothering our bread

with it when she wasn't looking. Sometimes, she would even take the butter off

the table if she thought we were using too much. We also had a chicken pen and

my mother would preserve eggs in Isinglass for the winter. Occasionally, we

would even have a chicken for dinner on Sundays. We raised our own chickens

with the help of a clucky hen. I still remember my mother borrowing a hen from

our neighbor to sit on the eggs and hatch our chicks. When the chicks were old

enough, we would return the hen and give our neighbor a few young chicks in

return. We also sold a few quarts of milk each day, but it didn't bring in much

money. Sometimes, we were even paid with nothing at all, but my mother never

complained. One day, my mother was walking home after helping a woman who had

just given birth. The doctor would always call upon my mother for assistance if

needed. On her way back, she passed a house where a woman with six young

children lived. The woman called out to my mother, saying, "We don't even

have a piece of bread to feed the children." My mother then asked me to

take a double loaf of bread to the woman, instructing me to hide it under my

coat so my father wouldn't see it. However, as I was leaving, my father noticed

the bread and asked where I was going with it. He scolded me and told me to put

it back, saying that he didn't work hard to provide for the family of a man who

spent all his money on alcohol. After my father went back to work, my mother

gave me the bread again and told me to take it to the woman without my father

knowing. She couldn't bear to see children go hungry, even during the hardships

of the Depression. In 1932, the worst thing happened. We used to give Blossy

our vegetable peelings as a treat, and she loved them. One night, I brought her

home from the pasture at 5 o'clock as usual. However, someone had forgotten to

remove a potato from the peelings, and Blossy accidentally swallowed it. She

became bloated and started choking. My mother sent for our neighbor, who was a

blacksmith, to help us. He tried pushing a broom handle down Blossy's throat to

push the potato down, but it didn't work. Sadly, she passed away that night. My

siblings and I were heartbroken, but it was an even bigger blow to my parents.

We were left without milk, cream, butter, or curds and cream. It was a

disaster.

My father was speaking to a man from a vessel

that had just arrived from Prince Edward Island. The man mentioned that they

had black and white cows on the island that produced three times more milk than

a Jersey cow. He also mentioned that these cows were not expensive. My father

was intrigued and decided to borrow $50, which was equivalent to a month's

salary, from his boss. He then sent my mother on the produce boat to buy one of

these cows. The owner of the boat charged a small passenger fee for my mother

and promised to bring back a cow for her. I remember watching the two-master

vessel leave the harbor from our kitchen window. It left us kids in a frenzy as

the boat was old, leaked, and constantly needed to be pumped. After five days,

the boat returned and we saw a black and white cow on the deck, strapped to

whatever was available. We quickly ran to the wharf to see the cow. My father

used a hoist, which was usually used to haul up fish, and a piece of canvas to

lift the cow's stomach. Finally, she was standing on her own four legs again.

We then put a halter on her and a rope to lead her from the wharf to our barn.

Our barn became a busy place with many people coming in and out to see the blue-ribbon

cow that my mother had paid the full $50 for. For the first few days, we tied

her to a rope and stake so she could graze on the grass behind the sheds and

stores near our house. However, the first time my mother tried to milk her, the

cow kicked over the bucket and we lost all the milk. We lost a few more buckets

of milk before we could manage to milk her. We had to hold a dipper in one

hand, milk with the other hand, and keep the milk pail far away from the cow's

hooves because she was a real kicker. Finally, my mother thought I was ready to

handle milking the cow, so she sent me out to do it. She watched as I started,

and after a few kicks at my milking stool, I was able to milk into the dipper.

It was strange for me, as our previous cow, Blossy, would let us put the pail

down and milk with both hands, making the job faster. However, we had deadlines

to meet, such as taking the cow out to pasture and going to school. One

evening, when I was alone, I tried to rig up two poles under the cow and

against the barn wall to hold her legs back so I could milk with both hands. I

only had an old anchor to secure the poles, and they ended up getting kicked

off the wall, spilling the milk. After six months, we finally managed to tame

the cow and milk her with both hands. We discovered that she was a great

milker, and we never had enough pots and pans to hold all the milk. We were

able to sell more milk, which gave my mother a few extra cents to buy things

like a spool of thread. As we kids were growing up, we received old clothes

from our Aunt in Boston. My sister Carrie found a beautiful blue Celanese dress

in the bundle, and it fit her perfectly. She washed it and hung it on the

clothesline to dry. However, our beloved blue ribbon cow was grazing nearby and

ended up chewing off half of the dress before we could stop her. We had to keep

a close eye on the cow and make sure she was tied away from the clothesline.

This cow was quite a handful, always knocking down fences, and causing my poor

father to have to fix them after a long day of work. He cursed the blue ribbon

cow every day, whether we had milk or not.

No comments:

Post a Comment