Celia LeDrew

My mother's stories mostly about growing up in the 30s

Celia LeDrew BIO

Our First Xmas Tree

by Celia LeDrew

On Christmas Eve in 1929, the temperature dropped to seven degrees below zero, with a clear, crisp sky and a thick blanket of snow that crunched underfoot. After three days of snowfall, my father returned home from work early that afternoon. He chatted with my mother on the back porch before heading inside to grab his gun for hunting to prepare for tomorrow's Christmas dinner.

Papa always kept his guns high on the wall, far from our reach as kids. We watched him take down a shotgun before stepping outside, telling Mama, “If I can’t get any partridge, I know I can find a few rabbits.”

Mama was busy in the kitchen, skillfully preparing dinner from whatever she had on hand. She instructed us to watch from the dining room window for Papa's return, hoping he had brought home something for our Christmas feast. My brother and I gazed out at the sunset, the silhouettes of the spruce trees against the brilliant red sky resembling a Christmas card. We spotted movement on a small hill along the road and excitedly shouted for Mama, thinking it was Papa. She came to the window, only to tell us, “That’s not your father; there are two people, and he went hunting alone.” She returned to the kitchen, while my brother and I continued to watch, wondering who the other figure could be, since it was getting dark and seemed too large to be Papa.

Suddenly, Papa entered through the back shed door, carrying four rabbits. Mama was thrilled, as they would serve as our Christmas dinner. After the meal, Papa lit a lantern, announcing he would clean and skin the rabbits for Mama to prepare. When he opened the shed door, we noticed something else inside. Moments later, he came in with a lovely three-and-a-half-foot fir tree strapped to his back, explaining why we thought there were two people. It was the most beautiful tree I had ever seen, lush and perfectly symmetrical. Our excitement was palpable; we were finally getting a Christmas tree. The only one we had ever seen before was at the Mayor’s house, and not many families had them during these tough times.

Mama instructed us to clean up after dinner, promising we would decorate the tree afterward. Everyone helped out, although we had no ornaments, and I wondered how we would adorn the tree. Once the dishes were done, we gathered in the dining room. Mama brought in darning needles and thread, giving me a bucket of cranberries we had picked earlier that month and teaching me how to string them. My brother received a pot of popcorn, a rare treat for us. As I watched him string his popcorn, I noticed he was eating more than he was threading. I alerted Mama, who switched our tasks since no one particularly enjoyed raw cranberries. Once we finished, Mama told us not to hang the cranberries on the tree just yet, as she wanted to do it herself.

She carefully draped the strands across the tree and stepped back to admire it, deciding it needed something more. She handed my brother ten cents and sent him to the store for some molasses candy kisses wrapped in festive paper. When he returned, she showed us how to cut the thread to tie loops around the candies for hanging. As we sat by the warm glow of the Franklin stove, we admired our first Christmas tree, thrilled that we had something so special when no one else in town had one, except the mayor. My brother and I thought it needed a star on top, so we found an old cardboard shoe box, which crumbled as we cut it into the shape of a star.

As we glued it together, arguments broke out over the number of points the star should have—my brother wanted four, while I insisted on five. Mama, acting as the referee, declared my design the winner but insisted it was too large and needed to be trimmed down. We struggled with the scissors, re-pasting the points multiple times. My brother suggested we cover the star in silver foil, which we had saved from discarded cigarette packages, but it wouldn't adhere well to the cardboard. Then we remembered that Mama always bought Red Rose tea in a foil package. We quickly emptied the loose tea into a can, liberating the shiny foil. Soaking it in warm water, we prepared to finish our star.

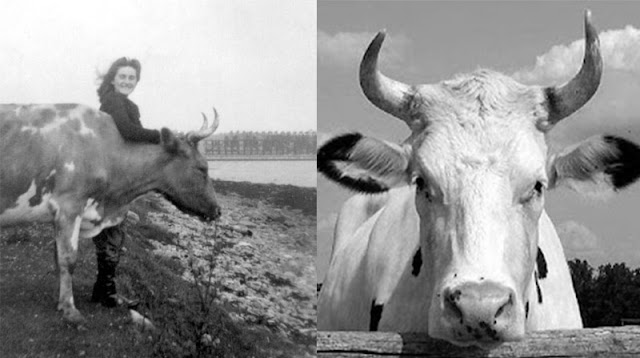

Mother's Blue Ribbon Cow

During the Great Depression, my family was

fortunate to have access to valuable resources. We lived near the sea and my

father was able to maintain his job, although his salary was reduced to only

$50 a month, a third of his previous earnings. Fortunately, he was also a

skilled hunter and fisherman, which provided us with a reliable source of food.

We even had our own fishing boat to catch fish for our meals. In addition, we

were fortunate enough to have a small barn where we raised two pigs for meat and

a cow for milk, cream, butter, and cottage cheese. We were constantly reminded

of how lucky we were to have these provisions during such a difficult time. Our

cow, Blossy, was a beautiful Jersey cow who was a beloved part of our family.

It was my responsibility to take her to the pasture every morning before

school. I would lead her on a rope to the pasture, which we rented for only

$3.00 a year. Blossy was a gentle and kind cow with the most beautiful eyes,

and it was always a pleasure to care for her. She never caused us any trouble.

In the evening, I would bring her back home for the nightly milking and keep

her in the barn until morning. It was a chore to care for the milk, and my

mother mostly took charge of this task. We had a separator to separate the

cream from the milk, and the extra milk was stored in large black pans until

the cream rose to the top. My mother would then scoop off the thick cream with

a spoon. Jersey cows were known for their high-quality cream. Later in the day,

we would use an old wooden butter churn to make our own butter. The remaining

milk was used to make curds, which were then hung to dry on the clothesline and

turned into cottage cheese. Curds and cream were a delicacy in our household.

Although we had an abundance of food, including homemade bread twice a week, we

also had salt fish and pork. My mother always reminded us to "go easy on

the butter," but my siblings and I couldn't resist smothering our bread

with it when she wasn't looking. Sometimes, she would even take the butter off

the table if she thought we were using too much. We also had a chicken pen and

my mother would preserve eggs in Isinglass for the winter. Occasionally, we

would even have a chicken for dinner on Sundays. We raised our own chickens

with the help of a clucky hen. I still remember my mother borrowing a hen from

our neighbor to sit on the eggs and hatch our chicks. When the chicks were old

enough, we would return the hen and give our neighbor a few young chicks in

return. We also sold a few quarts of milk each day, but it didn't bring in much

money. Sometimes, we were even paid with nothing at all, but my mother never

complained. One day, my mother was walking home after helping a woman who had

just given birth. The doctor would always call upon my mother for assistance if

needed. On her way back, she passed a house where a woman with six young

children lived. The woman called out to my mother, saying, "We don't even

have a piece of bread to feed the children." My mother then asked me to

take a double loaf of bread to the woman, instructing me to hide it under my

coat so my father wouldn't see it. However, as I was leaving, my father noticed

the bread and asked where I was going with it. He scolded me and told me to put

it back, saying that he didn't work hard to provide for the family of a man who

spent all his money on alcohol. After my father went back to work, my mother

gave me the bread again and told me to take it to the woman without my father

knowing. She couldn't bear to see children go hungry, even during the hardships

of the Depression. In 1932, the worst thing happened. We used to give Blossy

our vegetable peelings as a treat, and she loved them. One night, I brought her

home from the pasture at 5 o'clock as usual. However, someone had forgotten to

remove a potato from the peelings, and Blossy accidentally swallowed it. She

became bloated and started choking. My mother sent for our neighbor, who was a

blacksmith, to help us. He tried pushing a broom handle down Blossy's throat to

push the potato down, but it didn't work. Sadly, she passed away that night. My

siblings and I were heartbroken, but it was an even bigger blow to my parents.

We were left without milk, cream, butter, or curds and cream. It was a

disaster.

My father was speaking to a man from a vessel

that had just arrived from Prince Edward Island. The man mentioned that they

had black and white cows on the island that produced three times more milk than

a Jersey cow. He also mentioned that these cows were not expensive. My father

was intrigued and decided to borrow $50, which was equivalent to a month's

salary, from his boss. He then sent my mother on the produce boat to buy one of

these cows. The owner of the boat charged a small passenger fee for my mother

and promised to bring back a cow for her. I remember watching the two-master

vessel leave the harbor from our kitchen window. It left us kids in a frenzy as

the boat was old, leaked, and constantly needed to be pumped. After five days,

the boat returned and we saw a black and white cow on the deck, strapped to

whatever was available. We quickly ran to the wharf to see the cow. My father

used a hoist, which was usually used to haul up fish, and a piece of canvas to

lift the cow's stomach. Finally, she was standing on her own four legs again.

We then put a halter on her and a rope to lead her from the wharf to our barn.

Our barn became a busy place with many people coming in and out to see the blue-ribbon

cow that my mother had paid the full $50 for. For the first few days, we tied

her to a rope and stake so she could graze on the grass behind the sheds and

stores near our house. However, the first time my mother tried to milk her, the

cow kicked over the bucket and we lost all the milk. We lost a few more buckets

of milk before we could manage to milk her. We had to hold a dipper in one

hand, milk with the other hand, and keep the milk pail far away from the cow's

hooves because she was a real kicker. Finally, my mother thought I was ready to

handle milking the cow, so she sent me out to do it. She watched as I started,

and after a few kicks at my milking stool, I was able to milk into the dipper.

It was strange for me, as our previous cow, Blossy, would let us put the pail

down and milk with both hands, making the job faster. However, we had deadlines

to meet, such as taking the cow out to pasture and going to school. One

evening, when I was alone, I tried to rig up two poles under the cow and

against the barn wall to hold her legs back so I could milk with both hands. I

only had an old anchor to secure the poles, and they ended up getting kicked

off the wall, spilling the milk. After six months, we finally managed to tame

the cow and milk her with both hands. We discovered that she was a great

milker, and we never had enough pots and pans to hold all the milk. We were

able to sell more milk, which gave my mother a few extra cents to buy things

like a spool of thread. As we kids were growing up, we received old clothes

from our Aunt in Boston. My sister Carrie found a beautiful blue Celanese dress

in the bundle, and it fit her perfectly. She washed it and hung it on the

clothesline to dry. However, our beloved blue ribbon cow was grazing nearby and

ended up chewing off half of the dress before we could stop her. We had to keep

a close eye on the cow and make sure she was tied away from the clothesline.

This cow was quite a handful, always knocking down fences, and causing my poor

father to have to fix them after a long day of work. He cursed the blue ribbon

cow every day, whether we had milk or not.

Red Tape and Torpedo Nets

|

| Me and the barge (Gary LeDrew |

Rolling with their R's

In the 1930s, Canada was home to one of the most efficient ice breakers in the world - the C.G.S. MONTCALM. This impressive vessel was used to break up ice in the St. Lawrence River, as steel and coal were shipped from Sydney and Louisbourg. During the winter months, Sydney Harbour would freeze over, rendering it inaccessible to icebreakers. As a result, all shipping was directed to Louisbourg Harbour, which remained open year-round. When the C.G.S. MONTCALM sailed into Louisbourg Harbour, it was a moment of great excitement for the townspeople who would gather at the docks to greet her. This magnificent icebreaker was known as the most powerful one in the world at that time. The crew of the MONTCALM was mostly comprised of French individuals from Quebec. The Captain was English, while the Chief Engineer was a six-foot, curly red-haired Scotsman from Scotland. The crew members were welcomed by the townspeople and often attended social events in the area. One such event was the card games organized by the Catholic Parish, located about two miles from the town. These card games, usually a game called 45s, were accompanied by socializing and refreshments provided by the ladies of the church. One day, Margaret Murphy, a friend of mine whose father owned a local grocery store, invited me to join her for a card game. I had never played before, so she kindly dealt me a few hands to show me how to play. Despite my initial hesitation, I agreed to join her. That evening, the weather took a turn for the worse, with freezing rain making everything slick and slippery. Margaret had her father's old Chevrolet to take the Captain and Engineer to the card game. However, when we arrived at the store, we found that the sidewalk leading up to it was covered in a thick layer of ice, making it nearly impossible to walk on. I attempted to stand up, but ended up sliding down. Margaret faced the same fate. We ended up crawling up the incline on our hands and knees, with me opening the car door and waiting for Margaret to reach it. This took some time, and during that time, the Captain and Engineer engaged in a conversation while walking to the car. The Captain remarked that the Engineer spoke French very well for a Scotsman, but as he said this, he slipped and fell on his bottom, sliding down to the car. Margaret couldn't resist making a joke, saying that anyone would roll on their "r's" in these conditions. We managed to hold back our laughter as the Captain picked himself up. Margaret's father then threw ashes from the stove over the incline to make it easier for them to reach the car. Despite our slow and cautious driving, we still ended up being a little late. Upon arriving at the hall, we found everyone waiting to fill the last available table. We quickly joined them, and when asked why we were late and why we were laughing, we shared our story. This caused a great deal of laughter among the players, as the game of 45s involved players moving from one table to the next when they won. As a result, the whole room soon heard our story and joined in on the laughter. However, not everyone found our mishap amusing. The priest, Father Doyle, was not pleased, as he saw the card game as a serious event, not a circus. While some players were there to have fun and help with the church's funds, others were known as skilled card sharks who were solely focused on winning. Father Doyle was eventually informed of our story and, despite his initial disapproval, he couldn't help but laugh along with the rest of the room. As the game ended and prizes were handed out, everyone gathered for lunch, which soon turned into more of a circus. Father Doyle reminded everyone that it was not appropriate for some to be laughing so loudly while others remained unaware of the joke. In response, Captain O'Hearn stood up and explained our mishap to everyone, while the Chief Engineer added, "I am glad I rolled on my 'r's' as it made for an entertaining evening for all." Despite the initial disapproval, our mishap ended up bringing laughter and joy to all those present.

My Mother and the Nazi spy?

During the war in Louisbourg, my mother, Celia LeDrew (née Shaw), operated a boarding house at my grandfather's home on Commercial Street, right by the water near the government wharf and across from Cann's marine yard. She had a few boarders who worked at Cann's, including my father. One morning, the RCMP arrived with a woman and her two children—a young boy of about nine and his sister, who was around five or six. My mother was instructed to refer to the woman as Mrs. Smith and was cautioned not to disclose her presence to anyone, except to call for help if anyone came looking for her.

From what my mother gathered, the woman’s husband had been working in town as a dentist. He seemed wealthy and foreign, and after dating for some time, he proposed to her. She later discovered that he had married her in a rural Catholic church, with a friend posing as the priest while the real one was attending a funeral. They eventually moved to Ontario, where she learned he was German and an ardent supporter of Hitler. He raised their children to emulate Nazi behavior, ignoring their mother's attempts to guide them. He even possessed a secret shortwave radio and would sometimes vanish for days. Eventually, my mother could no longer tolerate the situation and sought help from the RCMP, who brought her back to Cape Breton. The children continued their Nazi antics, much to the dismay of those around them, and were often cruel to their mother, engaging in acts like putting the cat in a box and kicking it down the stairs. One of the boarders, Doug Hannon, intervened and gave the boy a good talking to.

One day, a local policeman arrived at our door with a stranger, claiming that the man was searching for his wife and children. However, when they turned to look at him, he had mysteriously vanished. My mother panicked, alerting the men who were having lunch, and they rushed to find him. She dashed upstairs and confronted the man as he climbed the back stairs. When he tried to shove her aside, she punched him in the mouth, knocking out three of his teeth. This delay allowed the police and the men to catch up and apprehend him.

The RCMP were called in and took them all away. My mother did not hear anything about the incident until ten years later when she received an anonymous letter thanking her and stating that the children had finally become well-behaved. It's worth noting that around the same time, there was a scare about a saboteur who was allegedly placing bombs in the coal used by the ships for fueling. My mother was a strong, determined Cape Breton woman, weighing just 118 pounds.

THE NEW SANDALS

PET SEAGULL BIDDY

Deer Meat and Hungry People

Deer season in Cape Breton Island during the Depression was one of the big events of the year. Everyone would be talking about it.

Weeks before the season opened I used to beg my father to take me with him as I loved to see the trees, birds, squirrels, partridges, pheasants- I was fascinated by everything that moved in the woods. My father always refused.

When I was 16 my father bought me a single shot, Colt 22 rifle. My father trained me with the gun to shoot the seabirds that came in the harbour quite close to our house and barn which were built on a breakwater. He taught me with old light bulbs we would get from the Marine Repair shop next door. They would bob up and down in the water with the waves, so he felt this was the best way to teach me. He said I should be able to shoot a few ducks when he was at work and our Labrador dog would fetch them in from the sea.

I had to shoot with a direct hit on three out of five bulbs. At first it wasn’t easy but after three or four times I shocked him by getting five out of five.

I loved tramping through the woods that could be so silent, until an animal or a bird would make a move. You must stand very quiet and still to make sure what you were shooting at. Silence is golden when you’re out hunting for food.

It was after the duck episode that I really wanted to go deer hunting but my father insisted it be not for girls. He said, “Never try to shoot a deer with a single shot 22 rifles, and don’t even try! And remember, there’s no such thing as an empty gun, even if it is empty!” We sure had to treat it as loaded.

The day the season opened my father took his 45 Winchester repeater and went off for a deer. He was gone only six or seven hours when he came home with his prize. All us kids could think of was a good hot dinner in the winter and we all seemed to be very happy about my father getting the deer so early in the season.

It didn’t take my father too long to prepare the meat for Mother to put in preserve jars and when the meat was prepared to her specifications out came the Mason jars, the big boiling pot to cook the meat. She would put in one row of meat in the jars and one row of bay leaves until the jars were full and added water. Then the jars were put in the big pot and boiled till the meat was cooked. Usually we had enough meat to do us for the winter but those who never went hunting or never owned a gun came to our back yard where my father was cutting the deer, everyone asking for a piece of the meat. No one was refused, but Mother was giving my father heck because she didn’t have enough preserved for the winter as he gave so much away.

My father told my youngest brother to get a license and asked him if he would try to get another deer to please my Mother. My brother took two days to get a deer and brought it home where every cut had to be perfect.

As he was cutting the meat, there had to be thirty or forty adults with a pot or pan or new paper saying, “I hope you have a piece for me.” I don’t think my brother ever looked up to see who he was giving the meat to. Most of the deer was given to other hungry people. Everybody shared food when plentiful, but he realized that he did not have very much left for my Mother.

There was lots of talk about giving away the most of the deer. Finally, my father said to my brother to take me up to the business office and get me a license (one deer one license.) This was my big chance. My father had taught me and trusted me with the gun and it was O.K. to go look for another deer. They were very plentiful that year, and this was the last day of open season. My father gave me his 45

Winchester repeater.

My brother took me through the swamp. Brush and woods so thick I thought I’d never get out of it. When we came across a small clearing, there were deer everywhere. My brother said, “Aim for the shoulder.” One shot and it dropped right on the ground. My brother said, “Get right over there and put another shot in the head “ (he had to point out where), “and kill it outright. Not a bad shot for a first time.” Then the worst thing happened that could happen.

My brother put his hand in his back pocket and pulled out the hunting knife and said, “Now go slit its throat, and bleed the animal.” I went around the deer in a few circles but fell to the ground. I don’t know how long I was there. My brother kept looking after the deer but stopped once in a while and with his hands scooped up some dirty swamp water and threw it on my face. When I came to my clothes were wet with swamp water, and mud all over me. Everyone in town ribbed me for years about always wanting to go deer hunting.

I never went deer hunting again and never killed a deer since. It was only for food, which meant so much to all of us in the depression in our town.

Many seasons afterwards the people that got some of the meat would always make sure when they saw me to ask if I would be going deer hunting this fall. Never! Never! Never! Once was enough to live down.

When mother prepared the deer meat, every piece of fat or sinew had to be cut off. The meat was soaked in salt water over night, then parboiled in baking soda, to take the game taste off the meat, then into the oven to roast. She always saved bacon fat to baste the meat so it wouldn’t be too dry. The same treatment was given to the sea birds to take away the fishy taste of the fowl. The birds were always roasted with bread dressing. We had much to be thankful for as the Depression was more of a case of survival and we were all made aware of it, and we were all in the same boat.

My parents were always teaching us to make things out of nothing. Mother was an excellent sewer and we wore hand me overs and hand me downs but Mother would make them to fit us kids so that we weren’t too poorly dressed. We never had new clothes for years. Mother would card wool and spin the yarn and we always had sweaters for the winter. She would dye the wool Royal Blue and Cardinal Red and the sweaters would always turn out to be red with blue trim or blue with red trim.

10 Point Buck

My father went deer hunting the next year. He was way back in the bush probably 5 miles from the road when he brought down the biggest deer he had ever shot. It was a ten point buck and he was very pleased.

He no sooner started to clean it when an American hunter came on the scene and offered him a hundred dollars for the deer. Papa said no thanks although it was very tempting. A hundred dollars went a long way in the thirties. But the pride of getting such a big deer won out and he had to cut it up into 3 pieces and make three trips to the road to take it home. All his life he would tell this story and finish it by saying. That deer was so tough you couldn't stick your fork in the gravy.

Hockey Game

Celia Shaw LeDrew

The Home On the Hill

By Charlie Shaw

We live at the house by the side of the hill,

A home away from home.

A better place you couldn't find

No matter where you roam.

For when the rain beats on the windows

Or the snow piles high outside,

Your sitting here in comfort

With your roommate by your side.

The nurses arc a kindly lot

They are always happy and gay.

They make your bed and clean your room

And bring meals on a tray.

Even those in wheelchairs,

They greet you with a smile."

There are a few exceptions,

They are a bit senile.

Sometimes we get so lonely,

And sometimes we blue,

But cheer up and do not worry

There's a lot worse off then you.

And when we die, we don’t know where we go.

For life is such a mystery that no one knows for sure.

We hope that we will meet again

On Heaven’s distant shore.

Now I'm speaking for my self alone

But what I say is true...

If you are good to people,

They will be good to you.

Charlie Shaw was my grandfather, he wrote this in a seniors residence in Sydney when he was in his ninties. he died when he was 96.

Celia LeDrew BIO

Cecilia (Celia) Margaret LeDrew Born April 1 1917 Louisbourg N.S. Parents Charles Shaw and Bessie Shaw (nee Snow) Celia was the fi...

-

Cecilia (Celia) Margaret LeDrew Born April 1 1917 Louisbourg N.S. Parents Charles Shaw and Bessie Shaw (nee Snow) Celia was the fi...

-

"When I was just eight years old, I stumbled upon a young seagull while exploring the beach near my house. Despite being newly hatched...

-

Our First Xmas Tree by Celia LeDrew On Christmas Eve in 1929, the temperature dropped to seven degrees below zero, with a clear, crisp s...